Purdue Fort Wayne professor weaves math into everyday life

By Blake Sebring

July 22, 2025

Something hanging on Hanan Alyami’s office wall says a great deal about how the assistant professor of mathematics education teaches students—and it’s not a diploma or an award. It’s an article titled “The Mathematics of Sewing.”

The work was published by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. It includes an overhead photo by Alyami’s graphic designer husband, Hamad Almakrami, and shows their 14-year-old daughter, Reema, twirling a nearly perfect circle while wearing a black skirt.

“I was talking about how I used the circumference formula to construct the skirt,” Alyami said.

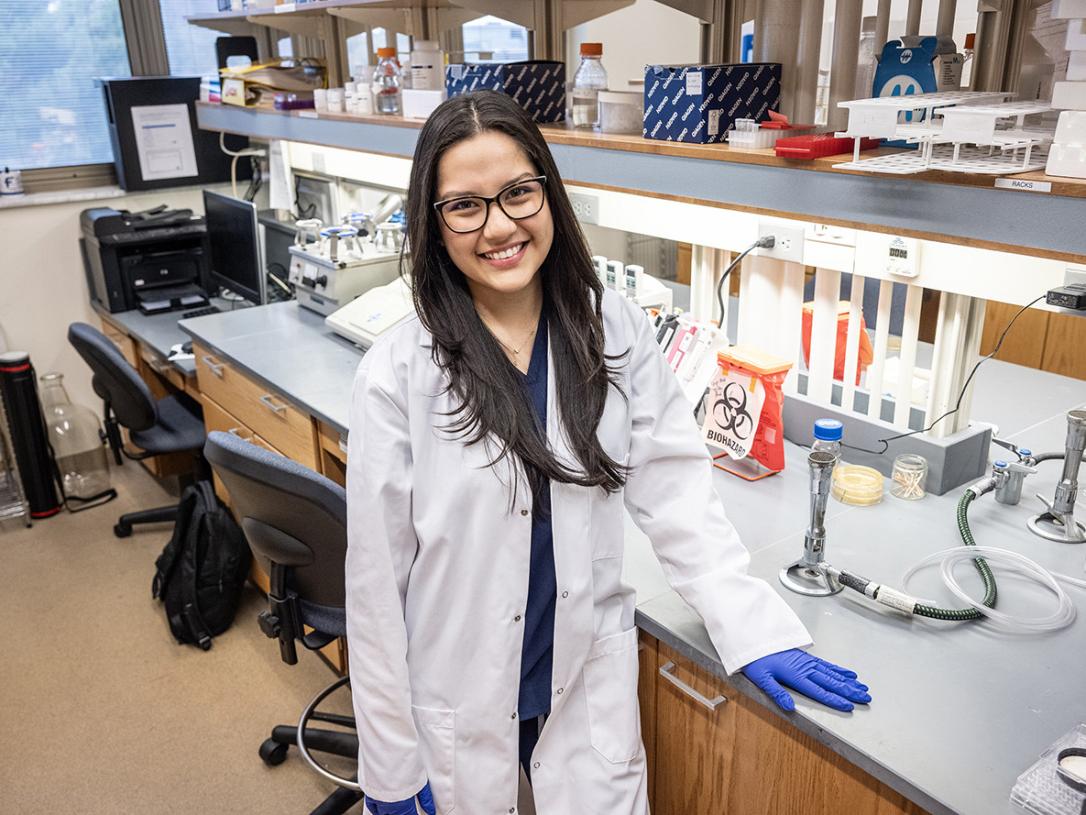

The article and photo show how Alyami, M.S. ’14, likes to use uncommon ways to look at and teach math. Last semester, she taught three classes at Purdue University Fort Wayne, primarily to elementary education majors learning to be math instructors.

Sometimes, her students may not view math as their specialty, requiring a mindset adjustment. Alyami admits she challenges their preconceived notions and fixed experiences because she believes everyone can learn math. That includes Alyami working on community building, encouraging them to meet unfamiliar classmates and publicly talk through their thinking and solution strategies.

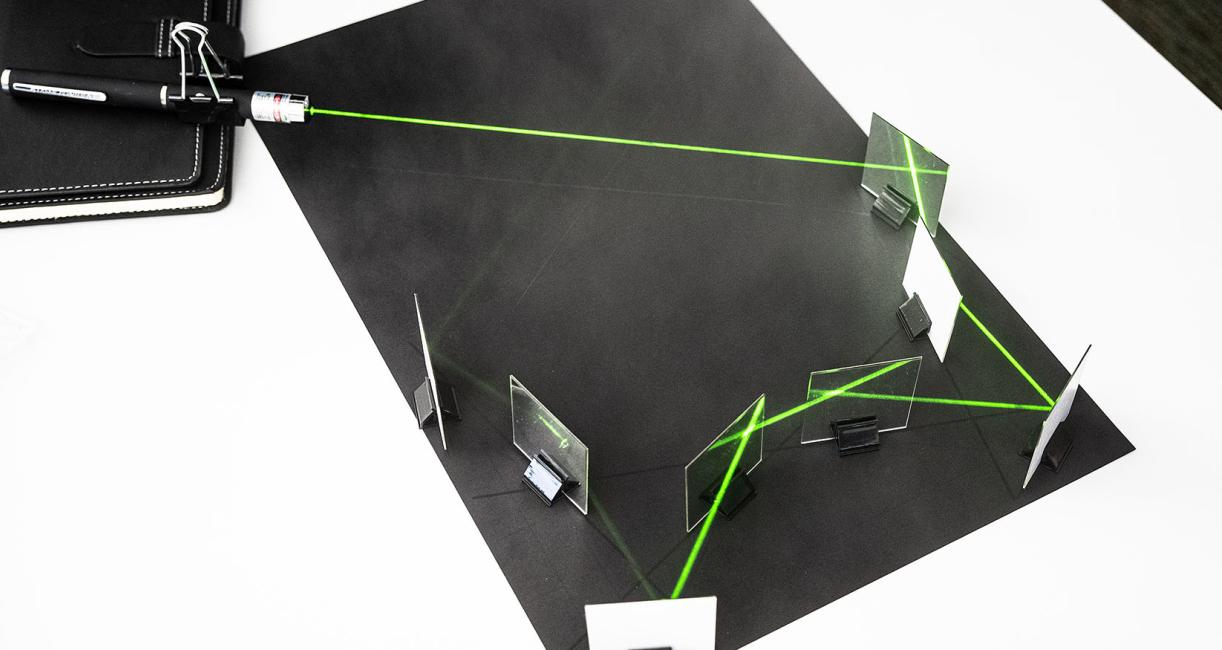

The problems Alyami presents may include mathematical situations or activities. One uses laser pointers with small mirrors to utilize light reflection as a mathematical representation of angle measure. It’s a way for students to make sense of geometry by creating mathematical designs that utilize angles and their measures.

Another uses 10 poker chips as two players alternate removal of one or two chips per turn, with the goal of not being the player who would remove the last chip. In another, students develop equations to tell which container will hold the most popcorn.

“I don’t thrive in math,” said senior Madalyn Moehring. “I didn’t want to do it. The first couple of assignments I turned in were super quick, just to get them done, and it definitely reflected in my grade.

“I think she could tell what I was doing, because as soon as I took the time to try and understand what she was trying to teach and actually put the work in to gain that deeper knowledge, my grades started to improve.”

Moehring has taken three of Alyami’s classes, one an elective problem-solving class, saying all were phenomenal.

“It kind of changed my view on math because now it’s not just a bunch of numbers,” Moehring said. “Now they actually mean something. I hope that every student gets to experience her because she’s truly amazing. She goes out of her way to show you that she cares.”

The point is, Alyami said, that everyone learns differently, and it’s her responsibility to help them understand the concepts and connections as much as the correct answers.

“I think the reason why I love math is because I don’t think about it procedurally, I look at it conceptually,” Alyami said. “Conceptual ways of thinking mathematically are really about the mental connections between different mathematical concepts. I think the students who struggle with math are the ones who might not have had the opportunities to make those connections.”

Recognizing students are going to learn differently, Alyami then needs to understand how they think so she can demonstrate those connections. As an example, she asks them to evenly place three fins around a rocket to produce the most stability. When students use different strategies, she asks, “How do these ideas connect, because they do the same thing?”

She’s not teaching the answers as much as helping them understand why the answer is correct.

“I believe people learn by constructing their own understanding,” Alyami said. “I can’t put the understanding in your mind. I present situations that might help your mind make those connections which would lead to understanding. Everyone can make these connections, and that ability to construct such connections is how learning takes place.”

That’s an important concept for math teachers to understand when they work with elementary students. With her activities, as Alyami said, students make sense of not just use of the algorithms and why they work.

“I’m not trying to make math fun, I’m trying to humanize it,” Alyami said. “A lot of the situations I present to my students are challenging for them, and they struggle through them, so it’s not really `fun.’ What makes it fun is the sense of pride they feel after going through productive struggle, constructing those connections and reaching their own understanding.

“This is how we learn. We value learning hard things because it feels earned, and I want students to earn their mathematical learning and understanding.”